Arte Now, Apocalypse Later

Filipe Marques

2014

até

28

June 2014

Círculo Sede

Registration open

17

May 2014

to

28

June 2014

Círculo Sede

“The present order is the future disorder.”

Saint Just

We can erect a historiographic device about the relationship between politics and the “natural” order of art and demonstrate that politics is one of the properties that are manifested in the body of experiences that we culturally place as art. Affirming that all artistic decisions and actions are political decisions and actions is on the same level as saying that we are alive before we die. Nobody escapes the violence of history, the confrontation between the principle of reality and the principle of pleasure, and what art is (what it can be and what they let it be) acts within the limits of power, is exposed to the notion of sovereignty, to the problems of free will, to the relationship between individual and State.

This political condition of art is, even more than Antigone, divided between obeying the laws of the sovereign (the patron, the State, the artistic system) or condemning itself. Even unsuspected English landscape designers were politicizing nature, introducing aesthetic values to which its flow, its discontinuity was indifferent, and incorporating into it the idea of the transcendent, simply because they turned their backs on the industrial revolution in which they were hopelessly immersed, the same revolution that, confident in its rationality, in its control of natural phenomena, in technical progress, imagined a world with a corrected and perfected nature.

To emphasize our thesis and even risking anachronistic nonsense, we can bring together the group of individuals who 17,000 years ago, in the Lascaux cave, dedicated hours of their precarious survival to realizing images capable of stabilizing an idea of memory and everyday life (images capable, also, of confronting this empiria with the very strong presence of the incomprehensible in the appearance of living and dead things); we can, he said, bring them closer (and to the community to which they belonged) to the words with which Jacques Rancière, starting from a reading by Plato, defines the political condition that, according to him, “begins when beings destined to remain within the invisible space of work that does not leave time to do anything else take into their hands, that time they do not have to assert themselves as people who also share a common world, to show what was not seen or to begin to hear as a word that discusses the common interest what was heard only as common noise”.

To leave “the invisible space (Gyorgy Lukács would call it reified) of work”, to resist (to rise up, to contradict... many verbs would fit here) in the face of the finitude of the lived, of the body and its automatisms, of dissociating oneself from the usual value of signs, of words (and, in addition, this difference can pass as happened with the Academy's neoclassical conventions by immobilizing the semantic function), are not these tasks of artistic practice? Isn't this your (inescapable) policy? To frame but also to decompose the larger disorder that is the real one? Living in lies to try, especially to try without success, to problematize the power of good to do evil and of evil to do good. Occupy another space in the real that is not defined and guaranteed by the mechanics (administrative, organizational) of command and obedience, of work and reward? A space practiced as the antithesis of the dominant doxa but also marked by its logos, by its historical contingencies, by its common places? A space that utopically dreams of the absolute autonomy of its means and objectives but that lives with the wild chaos of ideological struggles and the (increasingly) crowd divided between comrades, opponents and enemies.

But the awareness of the political value of artistic praxis is a relatively recent acquisition for art history. The awareness of this value (and effect) is symptomatic of the transformative changes that modernity has entailed for intersubjective practices and we can both place it in the way in which Goya introduces anonymous and heroic death into his painting Os Fuzilamentos de 3 de Maio (1814) as in the topic of alienation addressed by Flaubert in his Bouvard and Pécuchet (1881), both in the emancipation in relation to the non-historical report that the Fourth State obtained through Courbet's “democratic” painting and in the ideological indecisions between Self-criticism and revolution that defined the relationship of many avant-gardes with power.

The artist is faced with a monopoly on violence and he too wonders if he will give in to force, if he will be part of the order, he too is bought, he also shuts up. Or else everything happens the other way around. The way in which he problematizes his status as an author, how he negotiates the integrity of his work, how he accepts the other as an interlocutor, and finally, how he “goes down to the market” (to the system, which, we would say now, colonizes everything) to reveal his existence and eventually sell his products — according to Stefan Zweig, the poet Hölderlin commented that, too, he will come down to the market but that no one would want to buy him and this will be a characteristic of the modern creator, the (political) difficulty in constituting himself as a value of value Change or if insert into the social division of labor.

And what are the macro and micro politics of these self-representations in which art is political because it is art? We can summarize the repertoire to two general cases, the first will be the notion worn out today in the face of the spectacle of “official anti-art” (but a notion that was once vigorous), of the artist who presents himself as an uninhibited social person, as an adult who actively refuses the constraints associated with the social contract, the other, which combines romanticism and alterity, is the (self) representation of the artist as a motivational prophet who refuses the imitation of the world and anticipates, through the aesthetic revolution and the creation of the new, the aspirations for change that shape the Utopia with concrete life. Today, these two cases revert to artists who ideologically replace the universal with ethnographic alterity, implying the other, the foreigner, the uprooted, the non-specialist in inventing a critique of the present that aggressively focuses on that present. So from the experience of Agitprop From the Russian avant-garde to the isolated incursions of world-authors, the breach of trust (and the melancholy in the face of this finding is in some cases very strong) in relation to the obvious and the preconceived, has been permanently established in the relationship between the world of the supertechnical and the useless that is art and the world of Poloi, of the many that are no longer validated and no longer interact in the similarity but in the difference in relation to the established order.

As Clement Greenberg noted in his Avantgarde and Kitsch (1939), the “avant-garde moment” (modernism) is that of the estrangement of Western bourgeois culture in relation to its memory, it is the crisis of its symbolic values and of the capacity of artists (and poets, writers) to communicate (and be convincing in this communication) with their audiences; the avant-garde would be the cancellation (not only celebrated as in the futurist case, but problematized as in Mondrian) of this connection; it would be the irreversible historical moment, we say now, in which the utterance of art as a totalizing form ceases, revealing truth (and of an order underlying this truth) and therefore an essentialist one (the relationship between culture and its producers and detractors would never be the same).

Truth without an author ceases to exist for art and this is a political fact. And even the prescriptive agonism of the avant-garde that will result in the growing specialization (and loss of clarity) of their message, is nothing more than the exacerbation of this irreversible separation between art and truth. We are still talking about politics without stating it, especially if we think, as T.J. Clark does, that Greenberg sees the vanguard as the only instrument capable of preserving (through a meta-language and specialization) the culture of relativism, desolating kitsch.

One aspect to highlight is that the use of the political question (and insist on this point, a use not only read as the social construction of the author's sensitivity but as a working method where philosophy and its apories disturb the routine and the indulgence of doing, manufacturing, and the expected) is confronted with the errors and miseries of his recent history and today the temporal limits of the value of use of the art of propaganda must also be questioned (but the entropy resulting from Art as a discourse of art). It is true that the political value of art has been problematized (and reinvented) by antagonistic conceptions that place it symmetrically as a threat to the idea of difference, as a place of deprivation (an inferior, “commoner” moment in the artistic life of objects) or that place this value in a direct relationship with transformed reality, in a relationship that is situated, in conflict, in the heterogeneity of daily experience and of the abstract systems of power.

Perhaps the great learning from these mistakes and miseries is not so much in the monochromatism of the world. The world is immaculate and dirty, beautiful and ignoble, there will be guilt and innocence, selfishness and detachment; yes, the crowd is divided, there will be different levels and importance of “them” and of “us”, of managers and administrators, and violence is a historical procedure but the task needs to be less oriented towards black and white Manichaeism (because “we” can quickly become “them”) and to understand what makes men accept reality or reject it, Does it make men sell themselves to the devil or prefer to immolate themselves in fire of sacrifice. The artist doesn't have to answer (or even problematize) the central question that haunts us in scarcity, “to whom does the world belong?”. Their indifference or refusal is also a legitimate political act. The idea of politics at issue here goes beyond any reinvention of the politicization of it must be of art, nor does it refer to the migration from “being together in opposition” to the concept of a plural collective with a Voltairian root (dissent as the eternal gift of the idea of art).

Impossible conclusion. The general value of artistic tendencies can also be measured by the way in which they are inserted in a community and how at the same time they subvert the rules with which that same community defines (for itself and for others) the form and content of their experience, its memory, its codes and its limits; therefore, there is no absolute, deterministic truth in the relationship of artists (and the product of their work) with the world in which they live and with the regimes of oppression, domination, exploitation and naturalization of the institution that define that world. On the other hand, there is the possibility that knowledge, of the framework, of these modalities of control and social dismissal are based on artistic experience. There is the possibility of thinking artistically about what makes the real what it is.

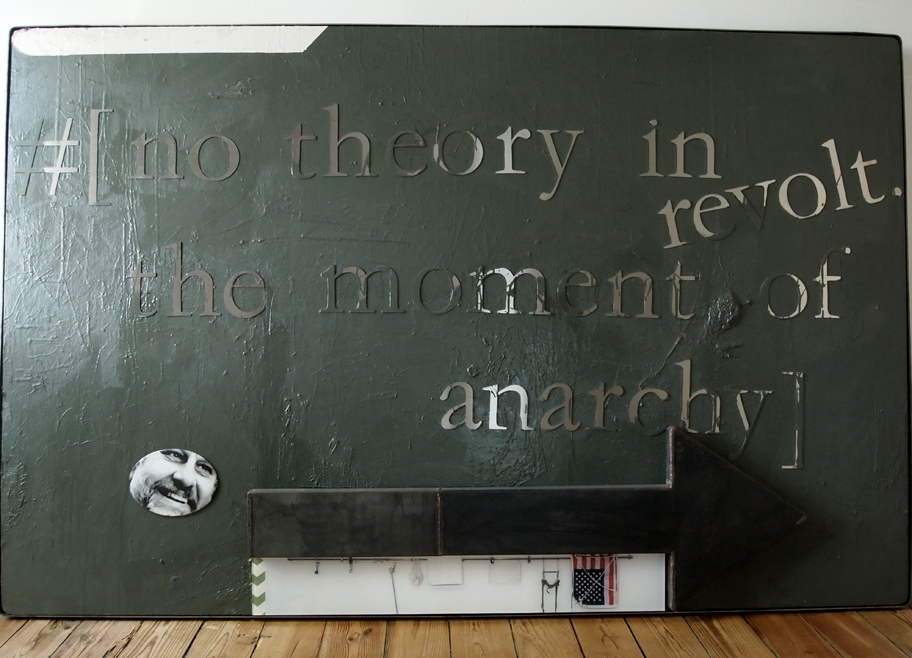

It is within the possibility of art being created as political and perceived as poetic or created as poetic and perceived as political that I enter the works proposed by Filipe Marques for CAPC; they denote a form of thinking with images who emphasizes the non-visual to contradictorily speak of the skepticism and finitude of the body, of the body in disorder, that lives in peril, that cannot leave the “sensitive work space” (he shouts, “pissing,” “ass”, “shit” but doesn't act).

The montage of the works is rooted in formal terms in the sphere of late-modernist power, in other words, it is problematized based on the reinvention of the rupture and the criticism of the naturalized community: the homeland, the language, the religion, the body, the monetary system are expressed in cruciform skiffs, in physiological interjections, in an experimentation of trial and error to overcome the problematic dualism between archetype (the desired form, the geometry of the utopian: the metal boxes, showrooms/showrooms of the static) and prototype (the flow of the lived, the existing being and acting in a way consumed by time).

These are methodologies that overdetermine the impossibility of anthropological reconciliation (there will be no harmony or consensus but struggle, it alone guarantees that the flow is not repetition but expectation, it alone guarantees that the future does not exist but that the present separates itself from the past). It follows that the central image of Filipe Marques's works, his combination of emptiness control and material semantics, is a work about that object that exists nowhere, about the counter-visuality of what separates us from the apparent, from the eternal return. Words eat up space and that's the only way it becomes radical.

Pedro Pousada

Automatic translation

Artists

Curatorship

Exhibition Views

Video

Location and schedule

Location

Localização

Educational Program

Associated activities

Exhibition room sheet

Acknowledgements

Notícias Associadas

More information

Technical sheet

Open technical sheet

Organização

Círculo de Artes Plásticas de Coimbra

Secretariado

Ivone Antunes

Texto

Pedro Pousada

Direção de Arte

Artur Rebelo

Lizá Ramalho

João Bicker

Design Gráfico

unit-lab, por

Francisco Pires e Marisa Leiria